The U.S. Should be Concerned with its Declining Share of Chip Manufacturing, Not the Tiny Fraction of U.S. Chips Made in China

Friday, Jul 10, 2020, 10:00am

by Semiconductor Industry Association

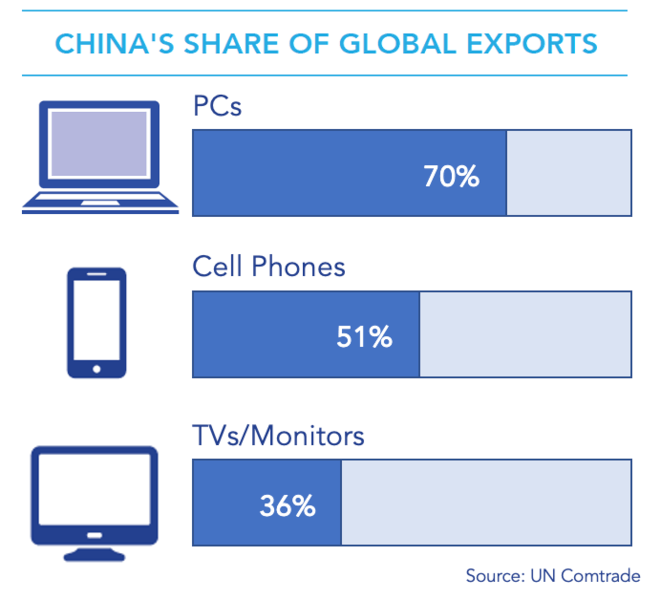

China has long been an important end-market for commercial U.S. semiconductors, accounting for over a third of all U.S. chip sales. That’s because China is the leading hub for assembling finished chips into circuit boards, which are then embedded into finished electronic products like TVs, smartphones, and laptops.

China has long been an important end-market for commercial U.S. semiconductors, accounting for over a third of all U.S. chip sales. That’s because China is the leading hub for assembling finished chips into circuit boards, which are then embedded into finished electronic products like TVs, smartphones, and laptops.

The $70.5 billion in U.S. semiconductor sales to China (36% of all U.S. chip sales in 2019) propels U.S. semiconductor industry leadership in what the Boston Consulting Group describes as a “virtuous innovation cycle” fueled by scale and R&D intensity. Sales to China’s large and growing market provide the scale for U.S. companies to fund high levels of investment in R&D back here on U.S. shores, from which come superior technology and products, which in turn reinforces U.S. market leadership & profitability.

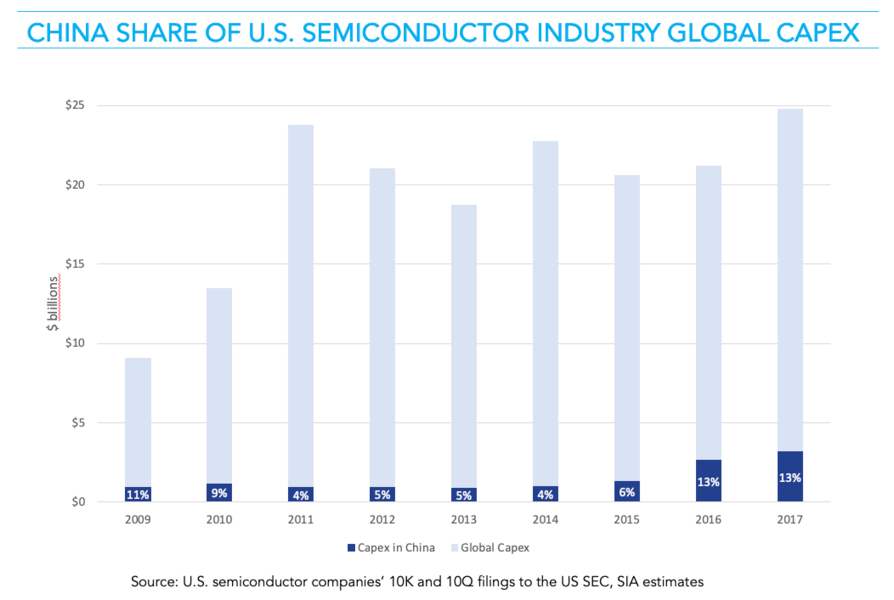

Some reports and policymakers have recently asserted U.S semiconductor firms are engaging in significant outsourcing of chip production to China. While indeed it is a major concern that the U.S. share of semiconductor manufacturing today only accounts for 12% of global capacity, and more chips designed by U.S. firms are made overseas than here in America, the reality is most U.S. chips aren’t produced in China. A recent U.S.-China Economic and Security Review Commission Report (USCC), for example, noted that capital expenditures by U.S. multinational enterprises (MNEs) on semiconductor manufacturing assets in China have jumped 166.7% from $1.2 billion in 2010 to $3.2 billion in 2017. The report, however, fails to view these investments through the lens of total historical global capex expenditures. While on its face this sounds like a lot of money and a very high rate of capex growth, when compared to historical U.S. industry annual capex spending, it’s comparatively small.

Indeed, the USCC report takes a very limited snapshot view, looking only at a single year and only at U.S. investments in China. In 2017, the U.S. industry spent $24.8 billion in global capex. Thus, the $3.2 billion spent in China in 2017 at the time represented roughly an eighth of all U.S. semiconductor capex spending that year. In fact, 2017 was an anomalous year in an otherwise flat trajectory for U.S. semiconductor capital spending in China. Seen cumulatively, from 2009-2017 U.S. capex in China represented an average of only 7.7% of U.S. industry total worldwide capex. As the chart below indicates, U.S. investment in China has been relatively low compared to total U.S. global capex. In fact, a very significant portion of capex spending has been outside of China.

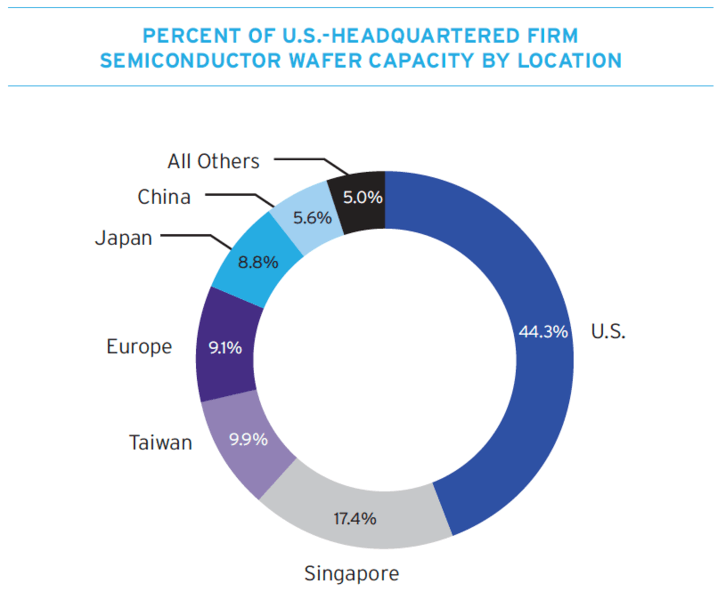

Upon closer review, the reality is China accounts for less than 2% of all U.S.-owned and operated fabs around the world, and a mere 5.6% of total global U.S. semiconductor industry front-end capacity. Forty-four percent of the fab capacity of U.S. semiconductor manufacturers is still based in America, with 70 fabs operating across 18 states. But as the accompanying chart indicates, many U.S. firms have chosen to expand beyond our shores (rarely in China) where more attractive incentives are offered.

Upon closer review, the reality is China accounts for less than 2% of all U.S.-owned and operated fabs around the world, and a mere 5.6% of total global U.S. semiconductor industry front-end capacity. Forty-four percent of the fab capacity of U.S. semiconductor manufacturers is still based in America, with 70 fabs operating across 18 states. But as the accompanying chart indicates, many U.S. firms have chosen to expand beyond our shores (rarely in China) where more attractive incentives are offered.

U.S. fabless chip design firms also conduct nearly the entirety of their production in non-Chinese foundries. Chinese foundries, such as SMIC and Hua Hong, captured only 5.8% of total global foundry revenue from U.S. companies in 2019.[1] Indeed, the bulk of U.S. fabless companies produce their chips in other parts of Asia. Additionally, while China is a rising hub for outsourced assembly, test and packaging (commonly known as OSAT or ATP), 70% of U.S.-owned ATP facilities are located outside of China.

Despite China being the largest single-country market for semiconductors, U.S. chip firms have deliberately chosen to locate the majority of their front-end manufacturing capacity outside of China. While China offers some advantages – close proximity to key end-market supply chains, low labor costs, and massive government incentives – weak IP protection, concerns over asset security, and lack of a sufficiently skilled workforce have been major inhibitors for U.S. semiconductor manufacturing investment there.

While China today is not a hub for U.S. semiconductor production, this does not mean the U.S. should rest easy. First, the U.S. declining share of chip manufacturing is a major concern. In an alarming trend, the U.S. share of global manufacturing capacity has declined from 37% in 1990 to just 12% today. Without more attractive incentives that rival incentives offered by other governments around the world, the U.S. will see a further decline as more fabs will be built in Asian countries – not the USA.

Second, aspects of China’s chip development pose major challenges for the United States. In fact, China is ramping up its own domestic semiconductor manufacturing footprint in ways that raise concerns. The Chinese government is funding the construction of more than 70 new fabs through a range of support measures, including direct subsidies, equity investments, reduced utility rates, favorable loans, tax breaks, and free or discounted land. As a result of these incentives, China’s global share of 300 mm chip production has grown 15.7% annually over the last seven years to 12% today, and China is projected to have the largest share of global chip production (28%) by 2030. So, China’s non-market industrial policies present challenges for the United States, but without an accurate diagnosis, we risk focusing on the wrong problem.

What is to be done? U.S. policymakers need to take action on two fronts – enable a stronger climate for chip fabrication investment here in the United States, while at the same time confronting China’s industrial policies through WTO-consistent trade policies and multilateral collaboration with our like-minded allies. Without action by U.S. policymakers, the U.S. share of global chip production will continue to decline in the face of these aggressive moves by China and other nations that prioritize domestic chip production as a national priority.

[1] Source: IC Insights’ 2020 McClean Report and related company annual reports